Spermidine is having a moment. The compound, which sounds like a portmanteau of “sperm” and “grenadine,” has exploded in popularity over the past few years, as indicated by Google search volume. Supplement sellers market it as an anti-aging molecule and peddle it in powder and pill form.

As you might have surmised, spermidine is definitely not a mixture of male reproductive cells and a sugary red cocktail ingredient (though it was originally isolated from semen). Rather, it is a polyamine compound found mostly in protein-making ribosomes inside cells. In the body, it controls various metabolic processes necessary for proper cell function.

Autophagy

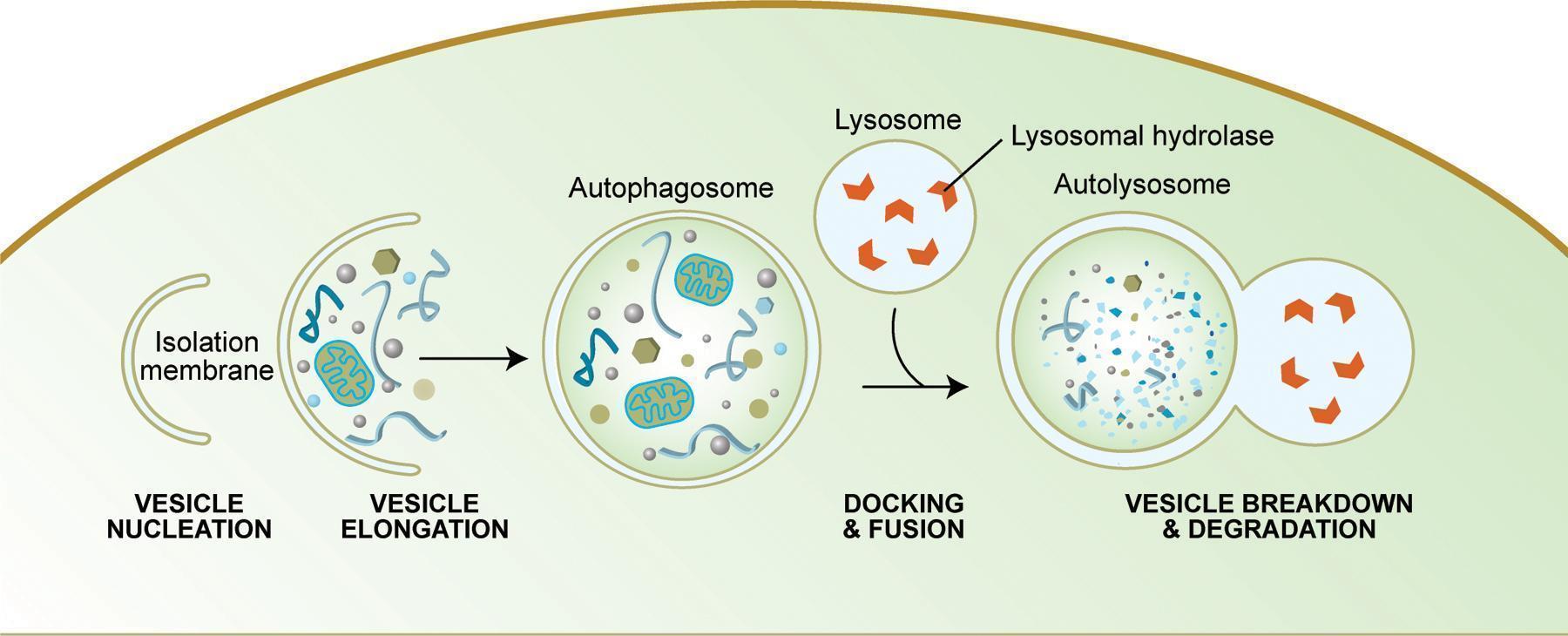

One of the things spermidine does is promote autophagy. Derived from Greek meaning “self eating,” this is the process whereby a cell disassembles damaged or degraded components and recycles them into new, better functioning parts. As shown below, a cell initiates autophagy by forming a vesicle and shoving whatever it wants to recycle inside of it. The vesicle, called an autophagosome, then merges with a lysosome, which is acidic and contains degradative enzymes. Following the merger, the contents inside are broken down and recycled.

Spermidine sellers tout autophagy as the molecule’s anti-aging “secret sauce,” so to speak, except they euphemistically label it “cellular renewal.” This slick salesmanship is not entirely unfounded. Numerous studies in model organisms show that spermidine supplementation extends animals’ lifespans, slows cardiovascular decline, protects against certain neurological disorders, and boosts liver function.

In humans, observational studies indicate that spermidine concentrations in tissues decline with age. They also suggest that people who eat diets rich in spermidine tend to live longer than people whose diets are lacking the compound. Spermidine is found in foods like wheat germ, fermented soy, soybeans, aged cheese, mushrooms, peas, nuts, apples, pears, and broccoli. Ingested spermidine is quickly absorbed from the gut and distributed throughout the body with little to no degradation.

So then does taking the stuff in supplement form slow aging and grant other health benefits? Frank Madeo, a professor of biochemistry at the University of Graz, has performed much of the research on spermidine in model organisms and has been building toward randomized clinical trials in humans for more than a decade.

Spermidine in clinical trials

The first of these was just published last year. Madeo and more than a dozen colleagues recruited 100 older adults between the ages of 60 and 90 and gave half of them a daily spermidine supplement and the other half a placebo. Over the next 12 months, the researchers monitored changes in subjects’ cognitive abilities and various physiological markers. When the trial ended, they found no benefits of spermidine over placebo.

As Madeo and his co-authors noted in their concluding remarks, it’s possible that the dose wasn’t high enough. But it’s just as likely, if not more so, that spermidine simply isn’t the “anti-aging” compound that researchers hoped it would be. The annals of science are littered with drugs that looked promising in animal trials but didn’t pan out in humans.

Spermidine is widely available and generally safe to consume at recommended doses, so it’s likely that additional human clinical trials will arrive in the future. Is it possible that these studies will have more glowing results than the first trial? Certainly. But like the spermidine available on Amazon, you probably shouldn’t put your money on it.

This article Is spermidine a legitimate anti-aging supplement? is featured on Big Think.

This content was originally published here.